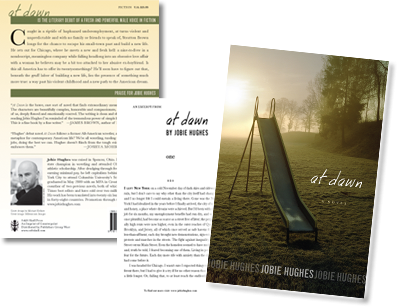

Excerpt from At Dawn by Jobie Hughes

I left New York on a cold November day of dark skies and sideways

rain, but I don’t care to say why other than the city itself had changed

and I no longer felt I could sustain a living there. Gone was the New

York I had idealized in the years before I finally arrived, the city of milk

and honey, a place where dreams were achieved. But I’d been without a

job for six months, my unemployment benefits had run dry, and work,

once plentiful, had become as scarce as a street free of litter; the perpetu-

ally high rents were now higher, even in the outer reaches of Queens,

Brooklyn, and Jersey, all of which once served as safe havens for the

less-than-affluent; each day brought new demonstrations, sign-wielding

protests and marches in the streets. The fight against inequality. Wall

Street versus Main Street. Even the homeless seemed to have multiplied

and, truth be told, I feared becoming one of them. Living in perpetual

fear for the future. Each day more rife with anxiety than the day that

had come before it.

I was headed for Chicago. I wasn’t sure I expected things to be dif-

ferent there, but I had to give it a try if for no other reason than to hope

a little longer. Or, failing that, to at least reach the endlessly evasive

mind-set in which I could stop making shitty, self-involved quips like

“hope a little longer.”

I had an old friend there who said I could stay with him until I found

a job and place of my own. I hadn’t seen him since high school and was

hesitant since he was precisely the type of person I wanted away from—

a deep family pedigree, pretentious, uptight, and, above all, successful

where I had failed. But he was a familiar face when the whole world felt

unfamiliar and just about the only option I had, so I took it.

I’d hoped to leave New York by plane but the cost of airfare would

have left only lint in my pockets. I considered taking the train, renting a

car, even hitching my way across the Midwest, but in the end I bought

a bus ticket and left it at that. I didn’t care how I got out. I just knew I

had to, and fast.

I boarded the bus on a Wednesday afternoon, soaking wet, out of

breath, carrying a green canvas rucksack full of everything I owned. I

had three hundred bucks and knew it wouldn’t last long. The bus was

half full. I sat adjacent to the only halfway decent-looking girl—modestly

pretty with shoulder-length dark hair, brown eyes and pale skin, the

feral brows of a twelve-year-old who’d yet to discover tweezers. She wore

low-rise jeans and leaned forward as I took my seat and I could see the

waistband of her panties. They were black. I closed my eyes and leaned

back, took a deep breath, affixed on my face the grin of a man sure of his

own luck, and suddenly looked forward to the fifteen-hour trip.

I was terribly hung over, freezing, still in the clothes I’d worn the night

before, which were now sopping wet. A ragged, thin jacket. Cold wind

coming in through several cracked windows. The bus wound its way

off Manhattan, sped through Jersey. After a half hour the rain stopped

and my clothes dried and I finally quit shivering. A movie showed on

dropdown screens but the girl beside me busied herself with a paperback

I wasn’t familiar with. I watched from the corner of my eye. She didn’t

seem to notice so I kept leering, hoping for an introduction to conversation,

at the very least another peek at her panties. I’m horrible with women,

always have been aside from a quixotic confidence that sometimes finds

me both fleeting and unpredictable. I was lucky enough to have been

born with blue eyes and what others have called good looks. Or, as a girl

I briefly dated once said: “You’re a very handsome guy. Maybe someday

you’ll actually realize it.”

The tires of the bus sliced through puddles of standing water that had

yet to drain. Cold and gray pressed against the windows, the landscape

paling away into a sunless murk, misty and somewhat eerie looking. I

was exhausted. I’d gone out the night before after convincing myself I

was celebrating new beginnings, but really I was trying to drink away

the emptiness my decision to leave had left me with. It was the right

decision, but not a single thing about it felt right; I didn’t really want to

leave, but the sad truth was that I’d grown desperate for some semblance

of direction. I’m a firm believer that things rarely change with a simple

change of scenery, but something had to give and it sure as hell wasn’t

giving in New York.

I’d gone out in the East Village. I’m fond of the dingier bars there,

the kind where your feet stick to the floor and a jukebox plays songs for a

quarter and quarters line the only pool table, the whole interior redolent

of flat beer and cigarette smoke and regardless of where you stand the

urine-soaked sanitary cube still finds you from the bathroom—which is

to say, the kind of bar in which I was raised.

I entered the first at six o’clock. It was empty. I had three beers and

left. A few people were at the second but I drank in the corner away from

them. I wasn’t in the mood for talk and instead pondered what I’d do in

Chicago and how my life would be different. I would make friends, not

always linger alone in the quiet interiors of bars and cafés; I wouldn’t try

to sleep with every girl I met; I would read as many books as I could, and

try finishing the one I’d already started; and even if it killed me, I’d find

a meaningful job to keep from undermining my always modest solvency

so that things might return to the way they were in the beginning, when

I first arrived, freshly printed college degree in hand. A hotshot ready

to take on the world.

I walked into the fifth bar after eleven and my luck turned for the first

time in months. The bar was half full. Loud music, laughter, intermittent

smells of perfume hanging in the air. It took ten seconds to spot Natalie,

a petite NYU grad student with dark hair and eyes who, for some reason

still unclear to me today, allowed a onetime unification four or five months

back. We’d met at a party on the Lower East Side. We were partners in

beer pong and we kept winning, which meant we kept drinking. We ended

the night at her place and, after undressing one another piece by piece

until, carefully and with an elated grin I hoped she couldn’t see in the

weak light, I slipped her lacy panties from her toned thighs and fell into

her with nothing short of drunken chaos, most of which I could barely

recall in the morning. She was the last person I had slept with. I was

lucky then and, having found her, felt lucky again, a feeling undoubtedly

bolstered by the eight or so beers I already had in me.

She stood talking to a tall man who wore a dark blazer and pressed

jeans, polished shoes, a watch that looked expensive even from as far away

as I was, and upon his face there resided the arrogant sneer and sharp

eyes of a privileged life. I wasn’t sure how to intervene.

I strutted into the bathroom and strutted back out, took a stool, twirled

my beer and tried emitting a level of self-assurance I knew I’d never pos-

sess, eyes slightly slanted while feigning indifference to everything around

me. Quiet confidence, I’ve heard it called. Natalie was being flirtatious,

laughing beyond politeness, touching the man’s arm or shoulder and

blushing at all the appropriate times. Her ass perfectly framed in dark

pinstripe pants, shiny hair past her shoulders gathering the light around

her. I burned for her as I sat and stared and tried recalling what she had

looked like naked that night and, when I couldn’t remember, I wondered

if I’d even seen her in the first place, that perhaps she was the shy type

who refused to undress until beneath the covers with the lights off. I knew

damn well she wasn’t the shy type.

The bar quickly filled. Two servers worked the floor and it was clear

that if I didn’t do something soon, then the opportunity would be lost. I

panicked. I couldn’t very well walk over and interrupt; a stronger, more

confident man could have, but not me, that wasn’t me anymore, and when

the server passed I impulsively reached for her and nearly knocked the

drinks off the tray she carried.

“I want to send a drink across the bar.”

“Tell one of the bartenders,” she said with a curt nod.

“I don’t mean the bar, to the woman in the corner.”

She looked to the corner, sighed, rolled her eyes.

“What do you want?”

Laid was the first thing that came to mind. Maybe a thousand bucks. Hell, I’d settle for a blow job. But then said, “A vodka and tonic.”

It was a ten-dollar drink and I tossed fifteen on her tray, which of

course was stupid of me, but I was drunk and in possession of the careless-

ness that typically comes with it. She walked away. I shook my head in

disgust. What did I really expect to happen, that Natalie would accept the

drink and rush over and fall headlong into me while claiming unbridled

love and asking herself how she’d survived these past five months without

me? No, of course not. It was a weak ploy and I was burning through

cash and still in New York.

I counted what money I had left but was too drunk and arrived at

three different numbers, none of which I found very encouraging. I put

my wallet away and spied the server marching toward the corner. A rush

of nerves. Why didn’t I walk by and casually bump into her, act just as

surprised to see her as she’d be to see me, make small talk until I could

weasel my way into the conversation? I was being a reckless idiot and

upon this realization my face grew flush.

The server handed Natalie the drink. She pointed at me and I smiled

and toasted the air, for what else could I do? Natalie squinted, looking

confused until it finally occurred to her who I was. She lifted her glass in

mere politeness, nothing more. She didn’t return the smile and instead

turned around and resumed talking to Moneybags, who grinned my

way, a grin that said he knew precisely what I was trying to do and that

I had no chance whatsoever of doing it. And he was right, of course, and

though I was already in a glum mood, it was at that very moment that

the incredible despair of my situation fully settled in. That was what my

life had come to in New York: barhopping, alone, the few people I had

once called friends all unsurprisingly busy for my going-away bar crawl,

and yet I still went along with it, equipped with the lone goal of running

into someone I’d slept with in the past so that I might sleep with her again

with none of the effort typically required—the arduous task I’ve always

called “punching the clock.” The futility depressed me, and the smart

thing would have been for me to save what money I still had and return

to the place I’d been staying to get a good night’s sleep and catch the bus

clearheaded and feeling good. But of course I didn’t. Instead I took the

man’s grin, his obvious success, as a personal affront, as a challenge, for

within it there was the unmistakable element of condescension, and the

last thing I needed was to be kicked in the gut when I was already down.

I waved to the same server and sent over another drink.

“You sure?” she asked, eyeing me with pity as though it was obvious

how this whole farce would end and the only person who didn’t know it

was me. But I did know. I simply chose not to care.

“Absolutely. And a Greyhound for me.”

I winked and threw a twenty on her tray. A few minutes later she

brought my drink and took Natalie hers. Hell, I wasn’t even sure her

name was Natalie.

She rejected the drink outright and shook her head while, just behind

her, Diamond Jim Brady stared, poised and intrigued. I flipped him

off and mouthed fuck you. He raised a brow and stepped forward and I

thought he was going to walk over. Instead he stopped short and, with an

air of authority, whispered in the ear of a large man wearing a staff shirt

I hadn’t noticed before, and in that moment it became clear that Daddy

Warbucks either owned the bar or had some stake in it. The bouncer

started my way, which in turn forced me into a furious race to finish my

drinks. I slammed the Greyhound, made it halfway through the beer,

when a hand slapped firmly down upon my shoulder.

“It’s time for you to say goodnight,” he said in a gruff, adamant voice.

“Fine,” I said.

I stood and turned. Through the endless clatter of voices and laughter,

I raised my arm and launched the half-empty bottle across the room. I

watched it sail through the air with ease, a thing of beauty if there ever was

one. That is, until it missed Moneybags by a good six feet and exploded

like a mortar shell against the exposed brick behind him.

I made to swing but another bouncer jerked me backward from

behind. I hit the floor. Somebody’s drink fell into my lap. My hands were

pinned behind me but I forced them free and threw errant punches that

struck only the air while catching no less than four to the back of my head

as they dragged me out. Just before we made it to the door I gazed back

toward the corner, and there stood Daddy Warbucks, flashing teeth with

a raised brow and his arm around Natalie, amused as though the whole

charade had been staged for his enjoyment.

I was launched through the air in the way of cartoons. I hit the pave-

ment and felt my phone break in my pocket. I rolled over onto my back

and stayed down for a full minute, staring up at the night sky, surprised

at how many stars I could see. A crowd gathered around me. A few asked

if I was okay. I didn’t answer because I wasn’t sure. Some offered hands

but I didn’t take them.

And then who do I see? Why, Mr. Cashman himself, standing tall

among the crowd, smiling his perfect smile down at me. He opened his

jacket and removed his wallet, plucked from within it a fifty-dollar bill,

and ever so casually let it slip from the tips of his manicured fingers. It

twisted and fluttered in the air like a butterfly and landed directly in the

center of my chest.

“Thanks for the drinks,” he said. “Now have a good night.” He turned

and walked back inside. I reached up and clutched the crisp fifty in my

right hand, thankful as hell to have it.